The Psychology of Stock Bubbles

We explore the psychological factors that create and reinforce stock bubbles.

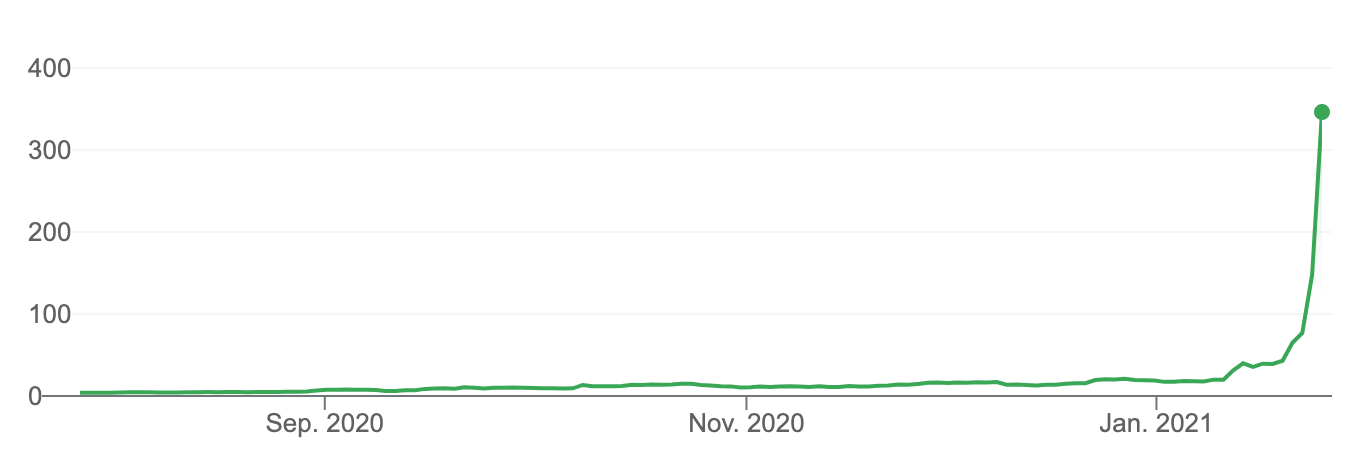

The recent 800% rally in the stock of brick-and-mortar video game store GameStop over the span of a couple of days, in the middle of a pandemic, seems to defy all laws of financial theory. Surely new information didn’t come forward so that the value of the business could suddenly grow 22 billions in just over 5 days. However, it is hardly the first time such bubbles have happened in individual stock issues. For example, Qualcomm rose a whopping 2,619% in the middle of the dot-com bubble before cratering when the bubble popped in 2000. And keep in mind that bubbles have been occurring long before the advent of technology and globalization. Back in the 18th century the Mississippi Company, a French trading company, rose 3,000% before losing more than 50% of its value the next year1. But what causes these bubbles to happen in the first place?

There is no simple answer to this question. Ask five different people and you will probably get five different answers. You might hear terms such as quantitative easing, asset bubble, short squeeze etc. A lot of articles have been written on these topics with respect to speculative bubbles. But I was more interested in the fundamental cause that allows bubbles to appear in general. I wanted to understand the reason for their existence, using first principles thinking. Would bubbles happen in a world full of perfectly economically rational robots? My answer was a resounding no and it surely doesn’t matter if these robots live on a negative interest planet. It therefore seemed obvious that the answer lies hidden in the inner workings of the human mind.

I found my answer in a rather unorthodox book, Poor Charlie’s Almanack, a collection of the thoughts and speeches of Charlie Munger, Warren Buffet’s lifelong investment partner. Known for his wit and multidisciplinary mind, the book is full of timeless wisdom not only on investing but on life in general. The talk that most interested me, The Psychology of Human Misjudgement, details Charlie’s framework for explaining why humans make irrational decisions. The framework consists of roughly 25 psychological tendencies that distort our perception of reality. When these factors synthesize in the same direction we tend to see large effects, a so-called Lollapalooza effect. And while some of these large effects can arguably be positive like the market dominance of brands such as Coca-Cola, other effects can be very irrational and lead to negative outcomes such as indoctrinating people into cults.

Suppose stock bubbles are an example of a Lollapalooza effect. What are the exact psychological factors that combine and cause people to abandon reason and take part in the madness of the crowds. Let’s take a look through the cold and hard objective lens of Charlie Munger:

1. Social Proof

When we see others take an action our brain convinces us that this is the correct action to take. A good example of this is the bystander effect where people are less likely to assist someone in need if more people are present and not doing anything about it. Another example is how effective social media influencers are at marketing products. Seeing someone popular use a product increases the chance of you buying it even though it says absolutely nothing about the quality of the product.

When we see a lot of people buying a certain stock the brain becomes more susceptible to leaving rationality behind because everybody is doing it. Therefore it must be the right thing to do.

2. Envy

Envy is a very powerful psychological tendency and can make intelligent rational people make very foolish decisions. Envy and jealousy are deeply rooted in human nature and can have disastrous effects. Stories since the dawn of civilization are filled with examples of how envy and jealousy are a recipe for a very unhappy ending. No wonder major religions had so much distaste for it. We have evidence of written laws from as early as early as the second millenium BC attempting to prevent the negative societal impacts of envy. The Code of Hammurabi, a code of 128 laws from ancient Mesopotamia inscribed on a stone pillar includes the following law:

You shall not covet your neighbor’s house; you shall not covet your neighbor’s wife, or male or female slave, or ox, or donkey, or anything that belongs to your neighbor.

I believe that one of the root causes of envy is found in how the human mind conducts measurement. It is well known that it doesn’t understand absolute values, all it knows is how to measure one thing relative to another. For example, a Yale study2 showed that when asked about wealth tax 50% of the public would prefer to earn less money as long as they earned as much or more than their neighbour. With that in mind it’s easy to see how stock bubbles trigger this psychological tendency and compel people to join in on the fun and not get left behind when their friends, neighbours and co-workers are getting rich.

3. Availability-Misweighing

The brain always overweighs information that is easily available to it due to its evolutionary short-circuiting cognitive system. Back in prehistoric times this gave man an advantage when fleeing predators but I’m afraid it has the opposite effect on his stock picking abilities. In my opinion, social media and the internet in general have made this effect much stronger than in the past because of how information goes viral. The distribution of media seems to follow a power law where 10% of the content dominates 90% of the space on online media.

Evidently this overweighs bubble stocks that are heavily featured in the news. So when investors need to choose where to deploy their capital they mostly look at what is right in front of their eyes. This also creates a vicious feedback cycle since more stock movement will cause more headlines which causes more buying which causes …

4. Overoptimism

A healthy dose of optimism can be an advantage when dealing with the hardships faced in life. However, the human brain has a tendency to overweigh the odds that are in its favour. The result is the existence of things such as lottery tickets and the colorful casinos of Las Vegas. The reality is that such bets have a negative expected value. This means that if you play enough games you are guaranteed to lose money. The house always wins.

Stock bubbles have an intrinsic misleading marketing material that reinforces this overoptimism tendency. Buying into stock bubbles gets mixed in with the term ‘investing’ and the stock price graph makes it seem like the probability of a loss is practically zero.And since the perceived risk is so low people are willing to put in more capital. Ironically, it would help if people thought about buying into a stock bubble like buying a lottery ticket. It would set expectations right. Many people lose a significant amount of their savings in a stock bubble but I haven’t heard of anyone going broke from buying lottery tickets.

5. Excessive Self-Regard

This tendency is probably pretty familiar to most of us. Some people might know this as the Dunning-Kruger Effect. In essence, our brain tricks us into thinking we are better than we really are at various skills. For example, Charlie cites a Swedish survey in his book where they showed that 90% percent of automobile drivers considered themselves above average. Now let’s apply this to a stock bubble. The stock is detached from its fundamentals and people only buy it on the premise that they can sell it to the next sucker for a higher price. And so on and so forth. Now considering that we’ve established that us humans are horrible at identifying that we might indeed be the sucker in question does this sound like a good idea?

All in all…

When numerous psychological factors like these five work in tandem it helps shine a light on why large irrational phenomenon occur so often in the real world. But knowing the cause doesn’t help in predicting when and where these bubbles start nor when they finally pop. Even Sir Isaac Newton couldn’t predict when the South Sea Company bubble popped and he ended up losing 20.000 pounds. That’s a little under 6 million in 2020 dollars to put that amount into perspective. After losing his savings Newton is credited to have said:

I can calculate the motion of heavenly bodies but not the madness of people.

and if Newton couldn’t it is very likely that you and I can’t. Denial of this statement would be a prime example of the excessive self-regard tendency. Remember that the only person that reliably makes money in bubbles is your broker.

As a parting thought I want to express that the intent of this blog post is purely selfish in nature. I have found with the help of Charlie that a good way to really pound some knowledge into your brain is to apply what you think you have learnt to current events. That is what I have tried my best to accurately do and it is almost surely riddled with mistakes. At the very least I hope that I, as well as you the reader, have slightly decreased our chances in the future of falling victim to the tricks of our own brains.

Further reading / listening

- Misbehaving: The Making of Behavioral Economics by Richard Thaler

- Psychology of Human Misjudgment by Charlie Munger (Youtube)

If you have any thoughts on this post shoot me a message on Twitter!