How Banks Create Money

An overview of how credit works in the banking system and the dangers it poses.

A very common view on banking can be summarized by the following statement:

Banks accept deposits from savers and then loan those deposits out to borrowers

This is a fundamental misunderstanding of how banking really works. The truth is that there’s no law that says that deposits need to be at least equal to or greater than outstanding loans. In fact, banks can loan out much more money than they have in deposits. Which leads us to the question, where does this extra money come from? Is it just created from thin air? The short answer is yes - it’s called credit and it’s much more widespread than you might think.

What is credit?

Imagine you go shopping at your neighbourhood grocery store. When you go up to pay for your groceries, you realize you’ve forgotten your wallet at home. Let’s say your groceries cost \$20. The clerk, knowing you’re a trustworthy person, writes on a slip of paper that you owe him \$20. You’re off the hook until the next time you visit the grocery store. Poof! The clerk just created \$20 dollars out of thin air.

Let’s explore why that is the case. You can now go home and spend a \$20 dollar bill that would have been used for groceries however you’d like. But the clerk’s slip of paper also functions as money, and this is precisely the money that was created. Who would have thought that grocery store clerks had the power to create money?

But how exactly does the slip of paper function as money? Let’s take our example a little further. It just so happens that the store clerk is a big cookie aficionado and your grandma is the best baker in town. The clerk can now visit your grandma and buy \$20 worth of cookies in exchange for the paper slip. You now owe your grandma the \$20 dollars you owed the clerk. The new \$20 worth of money created doesn’t exit the money supply (the total amount of money in the economy) until you pay up the debt and tear up the slip of paper.

From this example, we can see that credit is inherently built on trust. The clerk would have never issued the paper slip if he didn’t trust that at some point in the future, you would pay for your groceries. And for the paper slip to be functionally equivalent to money, it needs other people to trust it, not just your grandma.

The paper slip is what we call credit, which is simply an agreement between two parties on payment for resources at a later date. Note that credit inherently creates debt simoultaneously - the store clerk gets the credit but you have a debt to pay it back.

Banks function similar to the clerk in our example, except they do it on a much larger scale and there’s widespread trust in the credit they issue. In fact, most of what we normally call money in the economy is actually credit and only a tiny amount is cash, i.e. physical coins and bills.

To tie it all together, when a bank creates a loan, it enters a new number into your bank account with just a few taps, effectively increasing the total amount of money in the world. But is there any difference between this new money and the physical dollar bill in my hand?

What’s the difference between bank deposits and cash?

The difference between the terms credit, money and cash is blurry. In everyday life, bank deposits (credit) are treated as cash, and we refer to both as money. However, another common misconception is that:

Bank deposits are synonymous with cash

The assumption that these two terms are perfectly equivalent is erroneous, and although it is generally true this assumption breaks down under extreme conditions. Let’s explore what these conditions are.

A helpful trick is to think about bank deposits as being denominated in different currencies that are pegged to a national currency, such as the U.S. dollar, one-to-one.1 Let’s say that you are a customer of Bank of America (BAC). When you go to the ATM to withdraw cash, what you’re really saying is:

I’m going to exchange x BAC dollars for x U.S. dollars

And voilà, you’ve now converted BAC dollars from the chequing account stored on a computer server to physical U.S. dollars. This seems like a lot of mental gymnastics but bear with me.

When you went to the ATM to withdraw cash, the Bank of America had to find those U.S. dollars to give to you. Remember, credit is a promise for a payment in the future. When you originally deposited U.S. dollars into your chequing account, credit was created with a promise to pay you back your original U.S. dollars in the future. The credit was the BAC dollar amount displayed in your bank account. However this didn’t create new money since Bank of America still had your U.S. dollars in its vault. Meanwhile, Bank of America is free to create new money by making loans to borrowers. Creating loans means issuing more BAC dollars as bank deposits. And the bank deposits can quickly grow much larger than the cash in the bank’s vault.

Now, back to our question. Under what conditions does the assumption that bank deposits equal cash break?

What happens when Bank of America doesn’t have enough U.S. dollar bills when the time comes for your ATM withdrawal? It must sell some of its assets, like stocks, for U.S. dollars. If the bank doesn’t have enough assets, or the assets turn out to be very hard to sell, the bank runs the risk of defaulting on its obligations to you and becoming insolvent. And you might not get all of the U.S. dollars you deposited back from the bankruptcy process; for every BAC dollar you might only get 50 U.S. cents. This risk is one of the reasons banks cannot create an infinite amount of money. When a bank defaults, it violates our one-to-one assumption of BAC dollars to U.S. dollars and we can see why cash and bank deposits are not perfectly equivalent.

Any time the bank is forced to convert its own currency to U.S. dollars it has to find those U.S. dollars somewhere. This can happen when people transfer money to a different bank or make a cash withdrawal: anything that takes money out of the world of that bank. Keeping this much cash on hand is costly since it doesn’t earn interest2, so banks invest in long term assets such as stocks and bonds. The bank doesn’t want to be forced to sell those assets at an unfortunate time. In fact, massive selling could cause the value of those assets to plummet even further. This is why banks come up with ATM withdrawal limits, withdrawal fees and accounts with less flexibility to withdraw, like savings accounts. It’s all done to incentivize customers to refrain from forcing the bank to convert its made-up currency into the national one.

Insolvencies used to happen very frequently in the past and they are a long way from being extinct. A recent example is the British bank Northern Rock in 2009. The bank defaulted during the financial crisis and a lot of people lost most of their deposits. When people sense that a bank is at a risk of becoming insolvent, they will rush to withdraw their deposits. This is frequently referred to as a bank run3. The psychological herd mentality fuelling bank runs ironically increases the chances of the bank becoming insolvent. The bank might not be able to sell its assets for a good enough price all at once so the crowd’s fear of insolvency becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Summary

It’s a common misconception that banks loan out cash that has been deposited. A bank can, in fact, create money out of nothing via loans and it’s called credit. This works because bank deposits function as the bank’s own currency. If the bank issues too much of this currency it runs the risk of becoming insolvent. This often results in a bank run and the illusion that bank deposits are equal to cash is lifted.

When banks issue too much credit it is often referred to as a credit bubble. A credit bubble behaves in a lot of similar ways as stock bubbles (see my earlier blog post). Few people know it’s a bubble until it bursts. The stock and credit markets are systems controlled by the whims of humans and are therefore bound by the laws of psychology. It follows that we shouldn’t be surprised that they exhibit the same imperfections as human nature with all its heighs and lows.

If you have any thoughts or comments on this post shoot me a message on Twitter!

Further reading / listening

-

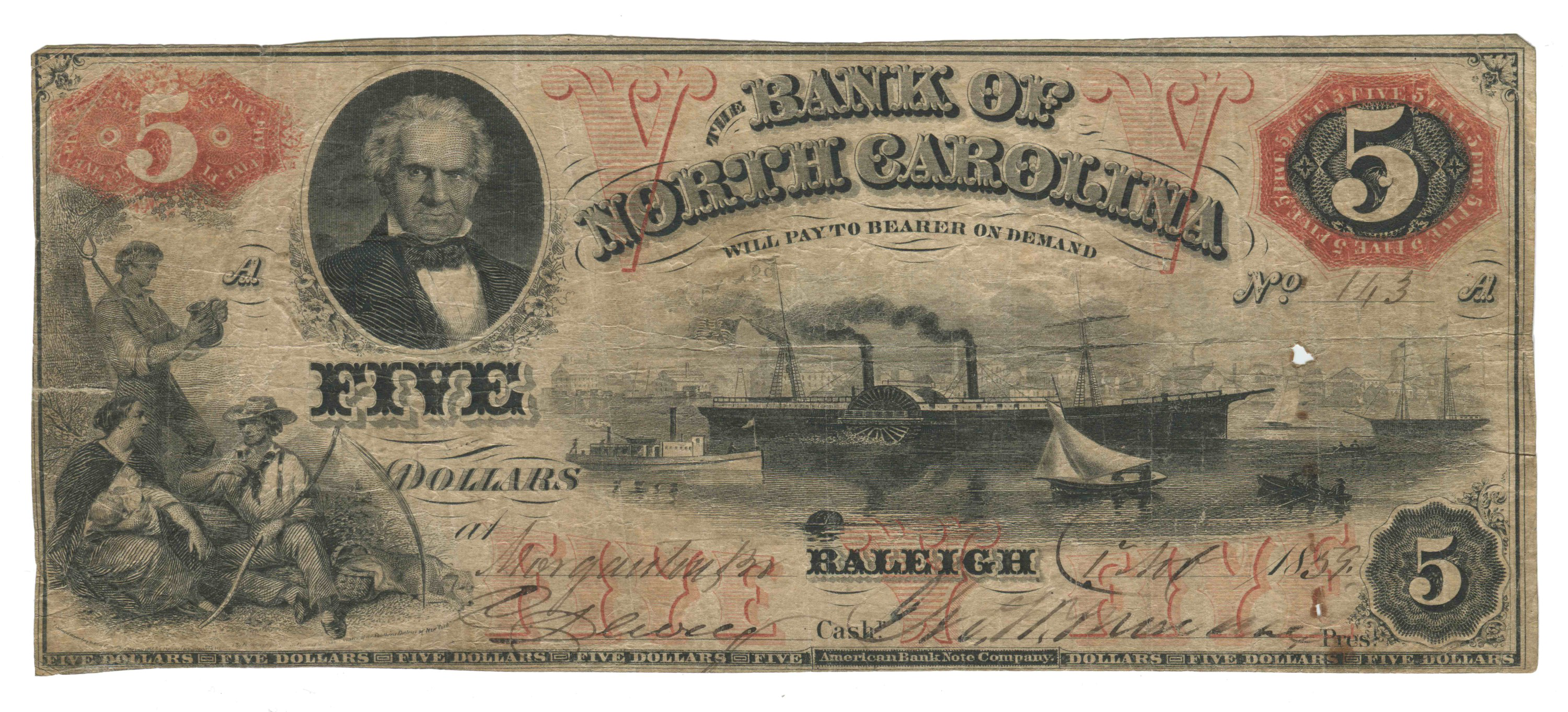

In the past this was exactly how banks issued credit. They printed their own bank notes, e.g. a Bank of America bill. This had a lot of problems including the bank notes with the same face value being valued differently depending on the risk of a particular bank defaulting. A hypothetical example: Bank of America note might be valued at 90 cents on the dollar while a Bank of New Hampshire note might be valued at only 80 cents on the dollar. ↩

-

Banks do earn some interest on U.S. dollars they store at the central bank. These dollars are called reserves and they are the only real digital version of the U.S. dollar. The reserves primarily serve the purpose of facilitating transactions between different banks and allowing them to withdraw cash when in need. They also allow the central bank to influence the interest rates in the economy by controlling the interest rate on the reserves. Interestingly in some places in Europe the interest rate on reserves is negative so that banks are better off keeping their reserves in cash in vaults which carries some negative interest through storage and security costs. ↩

-

Bank runs are partly solved with the government insuring deposits up to a certain amount. For example, the U.S. governement insures bank deposits up to a \$250,000 (as of 2021) through a program called FDIC (Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation) in chequing accounts. However if you’re over that limit and the bank goes bankrupt there is no guarantee that you’ll get your money back. This is a fundamental difference between physical currency and a bank deposit. ↩