Logistic regression from scratch

We derive logistic regression from semi-first principles using only our knowledge of linear regression, some basic probability and statistics, a dash of calculus and our good old intuition.

Outlining the problem

We have observations of dimensional data . For each observation we have a corresponding label . Now, we want to build a model that can predict a label given some unseen observation . Essentially we want to find a function that can model the following probability accurately

Since we only have two classes to predict we can keep our model simple with a single output

To build our model let’s start with something simple like linear regression and multiply our observations with a set of learned weights and add a bias to get our probabilities. Predicting the probability for an observation is then equal to

Let’s add an extra weight and to all our observations to remove the extra bias term and simplify our expression

So now we have a linear regression model. But notice how this does not work for classification since the model will output any real number instead of a probability. Our probabilities need to take on values between and so we need to somehow squash the output of our model.

Forcing our model to output probabilities

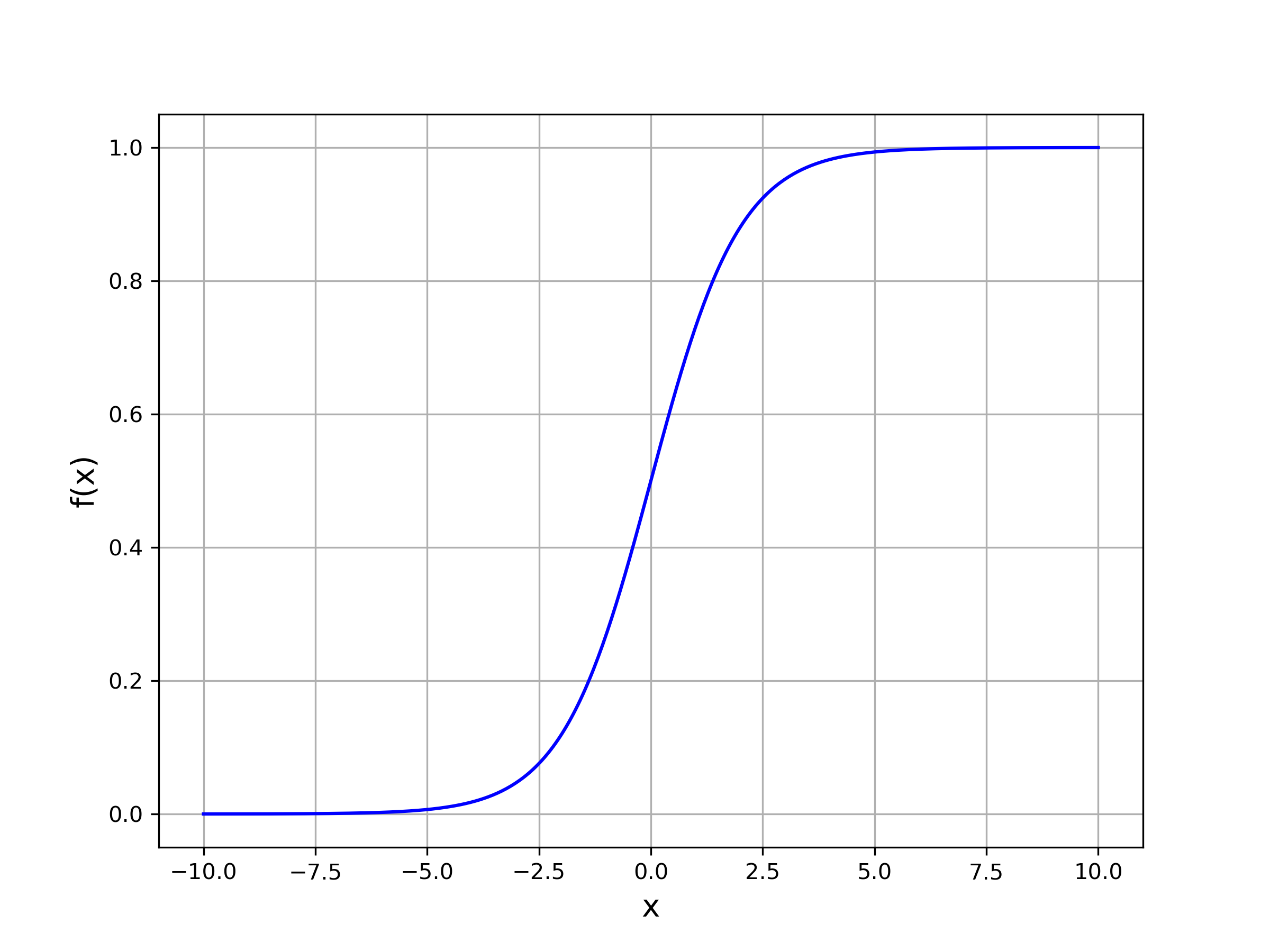

Now there’s several functions we can use to achieve this. Let’s start with looking at a function called the logistic function:

Notice how the function squashes our model’s output between and . Let’s plug in our linear transformation into this model and voila! Our model can now output a probability given an observation .

The intuition behind the logistic function

But why use the logistic function instead of some other squashing function? It turns out the logistic function allows us to interpret the output of the linear transformation, quite nicely. Starting with our model’s definition let’s solve for our linear transformation:

Multiplying with our denominator on both sides of the equation

Expanding the right side

Subtract from both sides and then dividing both sides with

Take the natural logarithm

Multiply by to isolate our linear transformation

Our linear transformation can therefore be expressed as

The fraction is not a coincidence, it denotes the odds of an event given probability . For example if the probability of an event is 80%, we can calculate the odds being 4:1.1 We can see that our model is trying to find a linear relationship between the log-odds and our input data . This is a key assumption of logistic regression, and this will help us interpret our weights just like in linear regression. For example, we can easily see how increasing a weight will correspond to a change in log-odds. Similarly, our bias term represents the log-odds of our model if our input vector is 0.

Finding our loss function

Now, we have our formula for making predictions, but how do we train our model so we can find the optimal weights ?

Basically we want to find such that , known as the likelihood, is maximized. This process is known as maximum likelihood estimation.2

Assuming our observations are independent this becomes:

Now products can be a bit of a hazzle to work with, they can be messy to differentiate and often run into numerical stability issues if we multiply a lot of small numbers. We can apply the natural logarithm here since it’s a monotonically increasing function and therefore doesn’t affect our choice of . Using the product rule this simply becomes a sum.

This formula is referred to as the log-likelihood. Conventionally, we minimize the negative likelihood which is equivalent to maximizing the log likelihood (NLL).

We can interpret as a Bernoulli trial with probability of success being , that is

Where the probability mass function for a Bernoulli trial is

Now, let’s enter our logistic model into the PMF

Finally, plugging this into the negative log likelihood formula above

Using the product rule for logarithm we can simplify this to

Finding the that minimizes the negative log-likelihood.

Our likelihood function does not have a closed form solution like linear regression. So we need to use a numerical optimization algorithm to find our optimal . A common choice is gradient descent, first we find the derivative of the function we are trying to optimize. Then take fixed size steps down the gradient until we arrive at the minima or in other words the optimal choice of that minimizes the negative log likelihood.

We’ll make one small change to our negative log likelihood. We’ll take the average of the likelihoods across our observations so that our dataset size doesn’t increase our log likelihood score. Our cost function is therefore defined as follows

Let’s simplify a bit further by using the rule for logarithms of fractions

And simplifying further

Now the gradient of the cost function w.r.t. is simply

Simplifying a bit we end up with:

And we recognize that fraction. It’s simply the logistic function! We now have all the tools we need to put this knowledge to practice!

Tying it all together in Python

Let’s generate some very simple dataset with two classes that are linearly separable.

# Make this reproducible

np.random.seed(1337)

# Define means and covariances for two classes

class_1_mean = [1, 1]

class_1_cov = [[0.25, 0], [0, 0.25]]

class_2_mean = [-1, -1]

class_2_cov = [[0.25, 0], [0, 0.25]]

# Generate n samples from the multivariate normal distribution for both classes

x1 = np.random.multivariate_normal(class_1_mean, class_1_cov, n)

x2 = np.random.multivariate_normal(class_2_mean, class_2_cov, n)

y1 = np.ones(n)

y2 = np.zeros(n)

x = np.vstack((x1, x2))

y = np.hstack((y1, y2))

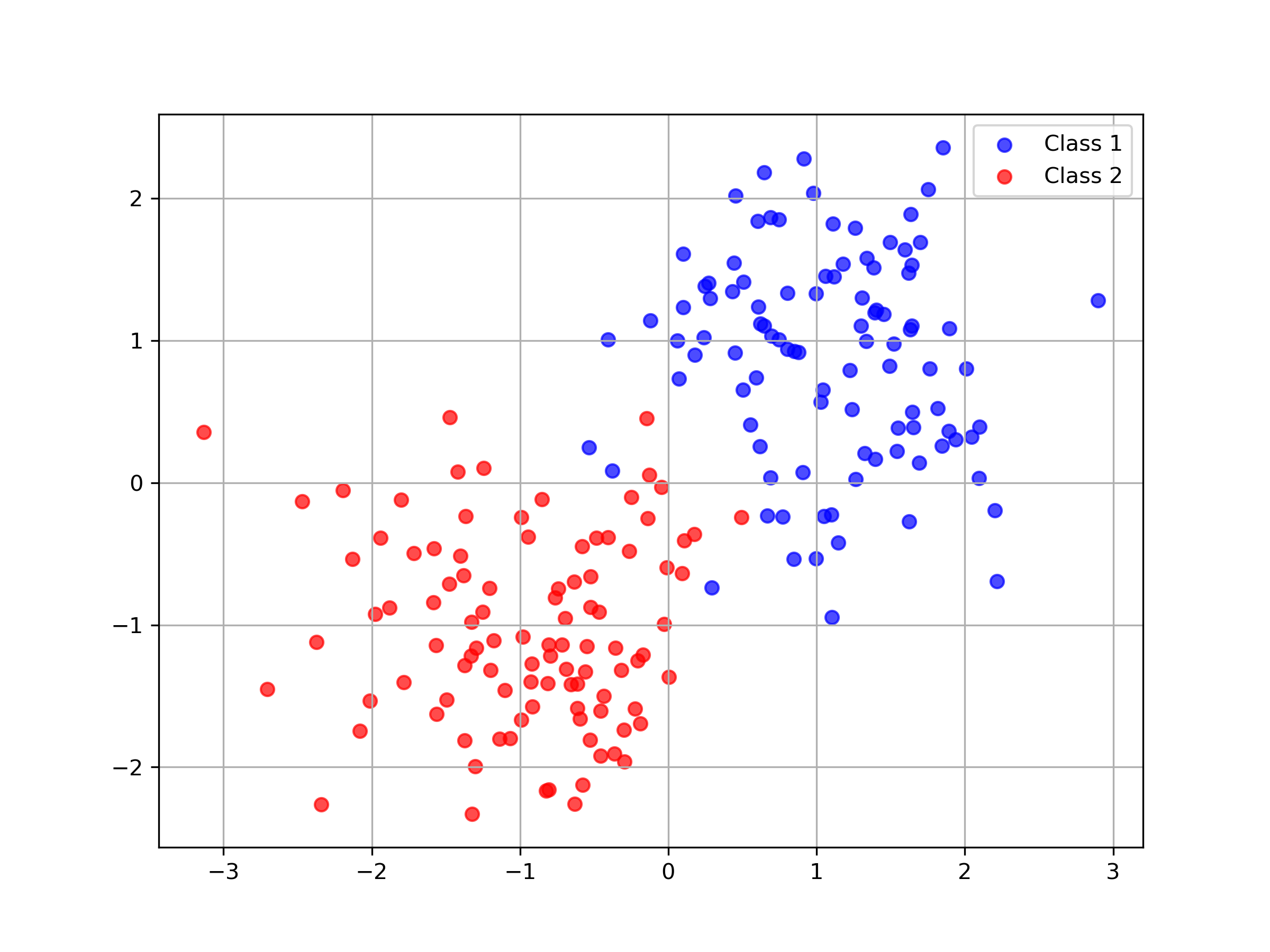

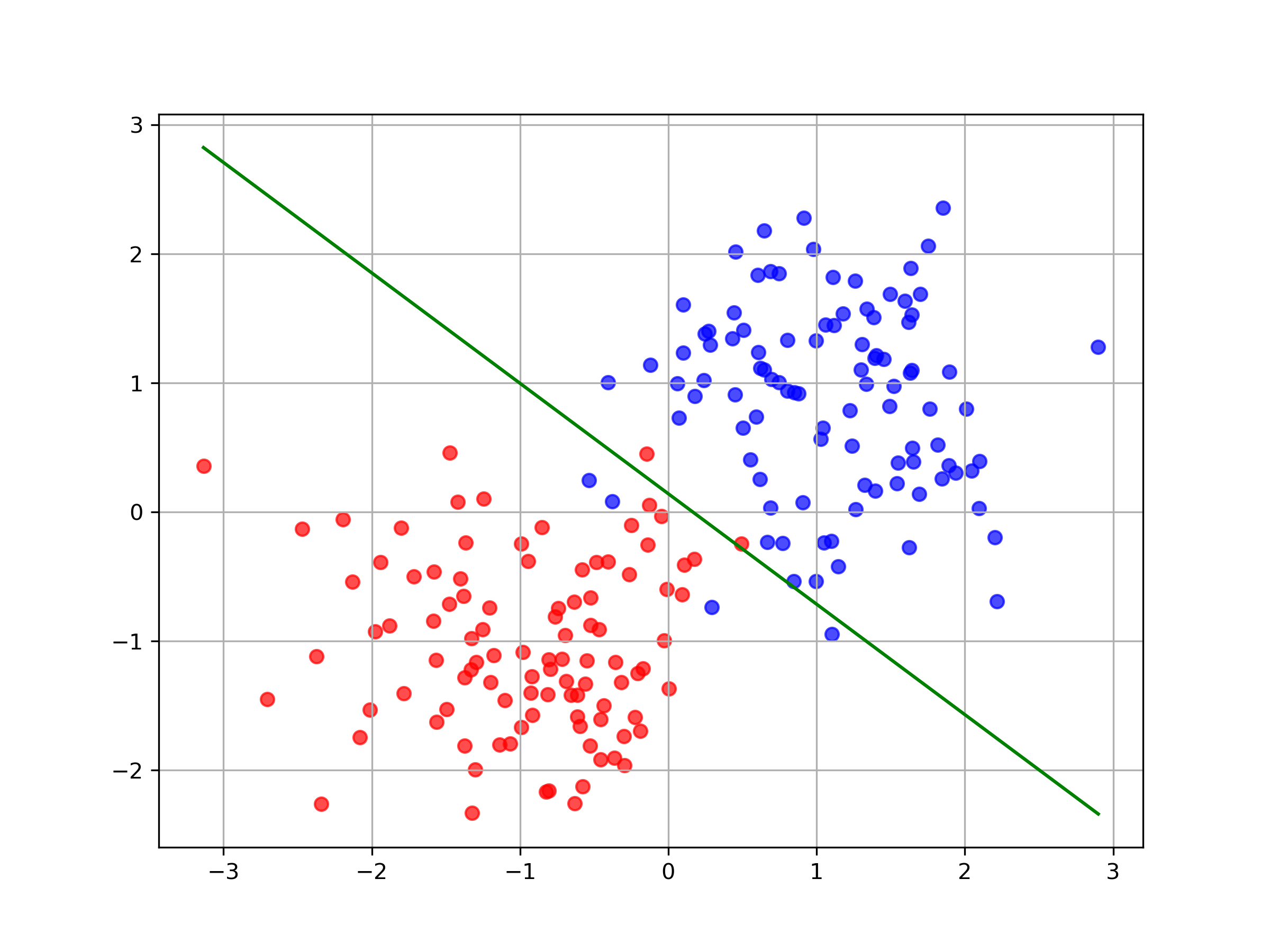

Plotting this data we get a nice figure. We can see that the data is basically linearly separable, our model should perform quite well here.

Now let’s set up our logistic regression model and how we train it so that the weights of our model are optimized. Note that there’s a whole wizardry field on how to optimize hyperparameters like the step size. For the purposes of this post we’ll just pick something reasonable.

def predict(x, w):

prob = sigmoid(x, w)

return (prob >= 0.5).astype(int)

def sigmoid(x, w):

return 1 / (1 + np.exp(-np.dot(x, w)))

def loss(x, y, w):

prob = sigmoid(x, w)

loss = -1/x.shape[0] * np.sum(y * np.log(prob) + (1-y)*np.log(1-prob))

return loss

def accuracy(y, y_pred):

return np.mean(y == y_pred)

def gradient(x,y,w):

n = x.shape[0]

return (1/n) * x.T @ (sigmoid(x,w)-y)

# Set up our hyper parameters

training_iters = 200

learning_rate = 0.05

# For reproducibility

np.random.seed(1337)

# Add a column of ones for our bias

x = np.hstack((x,np.ones((x.shape[0], 1))))

# Define our weight array, two for our dimensions and 1 for bias

w = np.random.normal(size=3)

# Let's train!

for i in range(training_iters):

w -= learning_rate*gradient(x,y,w)

if i % 10 == 0:

print("NLL is {}".format(loss(x,y,w)))

# Now that we have the model let's get out predictions

y_pred = predict(x, w)

print("Accuracy is {}".format(accuracy(y, y_pred)))

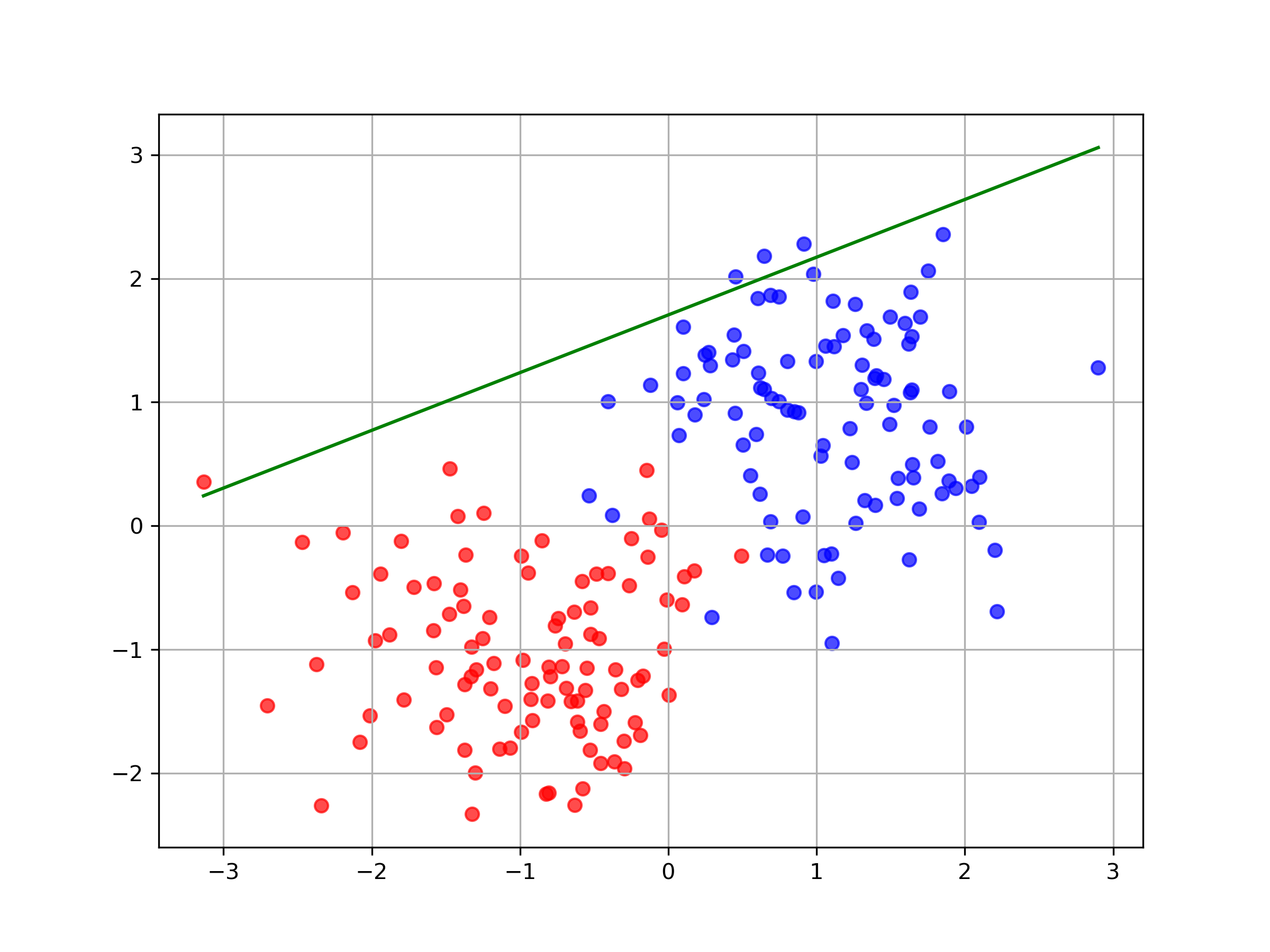

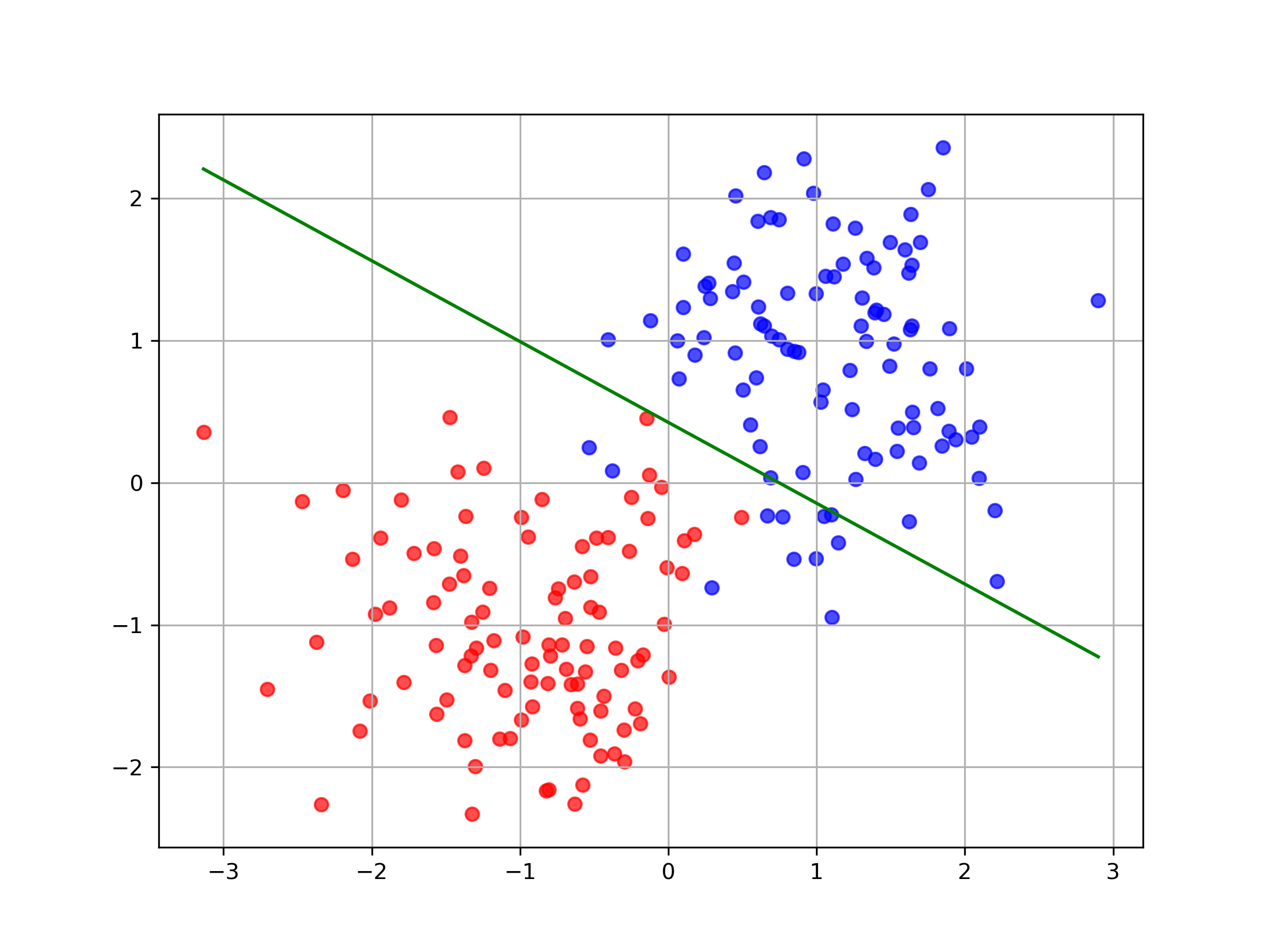

We can plot the decision boundary of our model: where at various points during the training process.

As expected, our model performs quite well on this data and quickly finds the optimal decision boundary. We get around 97% accuracy after couple of hundred training iterations.

A lot of what we covered: maximum likelihood estimation, normalizing raw predictions into probabilities, gradient descent etc. carries over to more complex algorithms. The entire code for the model training and the plotting can be found here.

-

This function of converting probabilities to log-odds is commonly referred to as the logit function and its output is known as logits. This nomenclature for the raw prediction of models before they’re normalized to probabilities has kind of stuck in the ML field even though we don’t really interpret the outputs as log-odds. ↩

-

This class of models is often called discriminative, i.e. we are only interested in the class given the data . But generative models focus on modelling the distribution of our observed data: ↩